Between 1821 and 1824 the project to build a railway in the North West, between Liverpool and Manchester, was taking shape but in 1825 the Stockton and Darlington Railway opened in the North East and, as a railway primarily built for the purpose of carrying goods, it successfully reduced the cost of carrying coal from 18s 0d to 8s 6d per ton. It quickly became apparent that high profits could be made by building railways. The initiative to build the Liverpool and Manchester Railway came from Joseph Sandars and William James and subsequently, a group of Lancashire businessmen, led by Charles Lawrence, Lister Ellis, Robert Gladstone, John Moss and Joseph Sandars asked George Stephenson to build them a railway between Liverpool and Manchester. The principal aim of the railway was to reduce the costs of carrying raw materials and finished goods between Liverpool, the most important port in the north of England, and Manchester, the centre of the cotton industry. The main difference between the Stockton and Darlington Railway and the Liverpool and Manchester Railway was that from the outset the latter was to carry passengers as well.

The proposed Liverpool and Manchester Railway was immediately seen as a threat to the Bridgewater Canal. This canal was making large profits by carrying goods between Liverpool and Manchester. In 1825, shares in the canal company, originally purchased at £70, were selling for £1,250 and paying an annual dividend of £35. Following the death of Francis Egerton, the Third Duke of Bridgewater, who had financed the construction of the Bridgewater Canal, a Trust was established to manage it. This initially consisted of three Trustees, one of whom was the Superintendent who was given supreme powers in the will of the late duke. It was this Trust, led by the Superintendent, which fought against the proposed railway. Turnpike Trusts, coach companies and farmers also voiced their strong opposition to its construction.

Parliament dismissed George Stephenson's proposed route for the railway and then James Sandars asked George Rennie (1791-1866) and John Rennie (1794-1874), sons of John Rennie Senior, to carry out a new survey of the line and they were also invited to build it. The brothers appointed Charles Blacker Vignoles (1793-1875) as their surveyor. At this juncture, George Stephenson disappeared from this project for a while. He had lost some position in the engineering world and he was embarrassed by making errors in levels. By hard work, he gradually regained his position.

The Enabling Act that empowered the Liverpool and Manchester Railway Company to make and maintain a railway between Liverpool and Manchester was passed on the 5 May 1826, 7 George IV Cap XLIX, and it consisted of 200 sections covering practically every aspect of the administration and operation of the new railway that the company was about to build.

An Act for making and maintaining a Railway or Tramroad from the Town of Liverpool to the Town of Manchester, with certain Branches therefrom, all in the County of Lancaster.

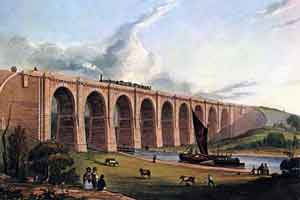

After the Act was passed, George Stephenson reappeared and took on the challenge of building the railway. He was immediately faced with a large number of difficult engineering problems. These included a 1¼-mile-long tunnel at Wapping, a 2-mile-long deep cutting at Olive Mount, the building of a 9-arched viaduct across the Sankey Valley and crossing the 4-mile-long unstable peat bog at Chat Moss. In order to cross Chat Moss, Stephenson relied entirely drainage and fill and in effect he floated the railway across it. He first put down cut and dried moss together with brushwood hurdles until an embankment of sufficient height and firmness had been formed. On top of this additional hurdles and faggots of heather and brushwood were piled and then covered with earth, sand and gravel. Finally, a thick coating of cinders was spread on which the track was laid.

The Liverpool and Manchester Railway was 31-miles long and it was built with a double track. The edge rails were of the fish-bellied type secured to stone blocks, later, to wooden sleepers. Passenger trains started at Crown Street Station in Liverpool but first they had to be hauled up an inclined plane of 1 in 96 by a stationary engine at Edge Hill where they were then attached to locomotives for their journey to Manchester. There were two stationary engines (one a backup) at Edge Hill and the engine house was disguised as a 'Moorish Arch' and trains passed below this. The architect was John Foster Jr of Liverpool. At Manchester, the railway line crossed the river Irwell to end on the corner of Water St and Liverpool Rd, where the station became known as Liverpool Road Station. Between Liverpool and Manchester, the railway line passed through, or nearby, Broad Green, Huyton, Prescot, Whiston, Rainhill, Newton-le-Willows, Kenyon, Worsley, Barton, Eccles and Salford.

At first, the directors of the Liverpool and Manchester Railway Company were in a quandary about hauling trains either using stationary engines, located at intervals along the line, or locomotives. To assist them in reaching a decision about this dilemma, they decided to hold a competition where the designers of the winning locomotive would be awarded the sum of £500. The idea behind this was that if one of the locomotives was good enough, then it would be the one used on the new railway.

The competition, which became know as the Rainhill Trials, was held in Oct 1829. Each competing locomotive had to haul a load of three times its own weight at a speed of at least 10 miles per hour. They were required to traverse twenty times up and down the track at Rainhill, which made the distance about the same as a return trip between Liverpool and Manchester. The load attached to each engine was to be three times the engine's weight. The judges were three prominent engineers: Nicholas Wood, chief engineer of Killingworth Collieries, John Urpeth of Stourbridge, for his services to the railway, and John Kennedy of Manchester, a wealthy cotton spinner and inventor. The trials began on the 5 Oct and they ended on the 14 Oct. The final three locomotives were Novelty (designed by John Braithwaite and Captain John Ericsson), Sans Pareil (designed by Timothy Hackworth) and Rocket (designed by Robert Stephenson with the aid of Henry Booth). The judges declared that Rocket had won the competition.

The village of Rainhill, where the trials were held, is about 8 miles east of Crown Street Station, Liverpool.

The Liverpool and Manchester Railway was opened on 15 Sep 1830 in the presence of the Prime Minister, the Duke of Wellington, and a large number of dignitaries. There was a procession of eight locomotives and these were the Northumbrian, Phoenix, North Star, Rocket, Dart, Comet, Arrow and Meteor.

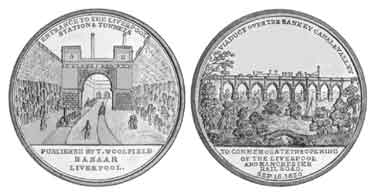

Medal commemorating the opening of the Liverpool and Manchester Railway.

Made by Thomas Halliday (1780-1855) of Newhall St, Birmingham. The reverse, left, shows the Moorish Arch and original Edge Hill Station at the bottom of Cavendish Cutting, Edge Hill, and beyond it are tunnel entrances. The obverse, right, shows the viaduct over the Sankey Canal and Valley near Newton-le-Willows with a train crossing. These medals were retailed at Thomas Woolfield’s Bazaar on Church St, Liverpool.

The Moorish Arch illustrated on the commemorative medal was a disguised engine house containing two stationary engines (one a backup) used to cable haul trains up two inclines. When the railway opened the passenger line between Crown Street Station and Edge Hill was cable hauled through Crown Street Tunnel. Similarly, the goods line between Wapping Goods Station and Edge Hill was cable hauled through Wapping Tunnel. Returning coaches and waggons descended by gravity. The original Edge Hill Station was in the deep Cavendish Cutting. The arch was demolished in the 1860s when the cutting was widened to facilitate a new track alignment.

Souvenir jug commemorating the opening of the Liverpool and Manchester Railway.

The opening celebrations included giving a number of VIPs a ride behind the Northumbrian and afterwards William Huskisson, a Member of Parliament for Liverpool, crossed from his own carriage to speak to the Duke of Wellington. Warnings were shouted when people realised that Rocket, driven by Joseph Locke, was about to pass the Northumbrian. In spite of these warnings, Huskisson was unable to escape and he was struck down by the Rocket. One of his legs was badly mangled and a doctor attempted to stem the bleeding. George Stephenson then used Northumbrian to take him to Eccles for further treatment but, despite all attempts to save him, Huskisson died later the same day at the Vicarage.

Following the accident, large crowds were still assembled along the railway line, so it was decided to continue with the procession. Nevertheless, when the Northumbrian entered Manchester the carriages were pelted with stones thrown by weavers who were aware of the Duke of Wellington's involvement in the Peterloo Massacre and his strong opposition to the the proposed Reform Act (passed in 1832).

In spite of such an inauspicious start, the Liverpool and Manchester Railway was an immediate success. In 1831 the railway carried 445,047 passengers. Receipts were £155,702, with profits of £71,098. By 1844, receipts had increased to £258,892, with profits of £136,688. During this period, shareholders were regularly paid out an annual dividend of £10 for every £100 invested.

|

|

Crown Street Station, Liverpool. This station and Liverpool Road Station in Manchester were the world’s first inter-city passenger stations and they both opened on the 15 Sep 1830. Crown Street Station was closed to passenger services on the 15 Aug 1836 to be replaced by Lime Street Station but remained open for freight services until 1972. |

The replacement Edge Hill Station, 1836. View looking westwards towards Lime Street Tunnel. This is one of the oldest railway stations in the world still in use. |

|

The four-track cutting, replacing Lime Street Tunnel, looking towards Edge Hill Station. The centre part is all that survives of the original twin-track tunnel of 1836 and it is 58-yards long. Due to increased use, Crown Street Station soon became too small and it was decided to build a new station at Lime St. To access this, worked started in 1832 on a 1⅛-mile long, twin-track tunnel which was completed in 1836. However, there were a number of accidents in the tunnel and problems with smoke. Consequently, in 1880 work started to open up the tunnel and widen the cutting to contain four tracks. This work was completed in 1882. |

|

|

The original Edge Hill Station and Moorish Arch at the bottom of Cavendish Cutting (aka Edge Hill Cutting), Liverpool. From right to left the three tunnels in the background are: Crown Street Tunnel (aka Stephenson's Tunnel, 1830) to Crown Street Station; Wapping Tunnel (1830) to Wapping Goods Station; and a storage recess. |

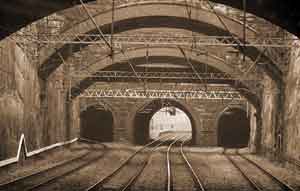

The bottom of Cavendish Cutting, 1930s. Crown Street Tunnel on the right is 291-yards long, Wapping Tunnel in the centre is 1¼-miles long and the additional goods tunnel on the left is 125-yards long. The latter was driven through the original storage recess in 1846. |

|

|

Olive Mount Cutting near Edge Hill. |

Sankey Viaduct near Newton-le-Willows. This is the earliest major railway viaduct in the world. |

|

|

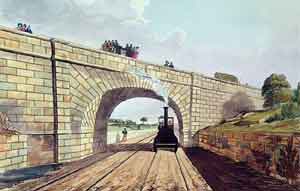

Rainhill Bridge. This skew bridge carries Warrington Rd over the railway. |

Chat Moss. |

|

|

Water Street Bridge, Manchester. |

Liverpool Road Station, Manchester. In this view the station is on the right with the station master’s house and Water Street Bridge to the left. This station was closed to passenger services on the 4 May 1844 when the railway was extended to Hunt’s Bank (Victoria Station) of the Manchester and Leeds Railway. It remained open for freight services until 1975. In 1847 the Manchester and Leeds Railway changed its name to the Lancashire and Yorkshire Railway. |

|

Victoria Station, Hunt’s Bank, Manchester. This view from Hunt’s Bank Approach shows the station as it looked when it opened in 1844. This single-storey building was designed by George Stephenson and it was built by John Brogden & Sons, a firm of railway contractors with iron and coal mines. |

Links

| Details | Grade | List Entry |

|---|---|---|

| The site of the original Edge Hill Station between Chatsworth Drive Bridge and the bottom of Cavendish Cutting with three tunnel entrances, including rock-cut side chambers. | N/A | 1476078 |

| Buildings on the south side of later Edge Hill Station. | II* | 1063311 |

| Buildings on the north side of later Edge Hill Station. | II* | 1218196 |

| Engine House on north side of Edge Hill Station. | II* | 1218206 |

| Accumulator Tower & Hydraulic Plant on east side of Engine House at Edge Hill Station. | II | 1359870 |

| Railway Bridge, Greystone Rd, Huyton-with-Roby. | II | 1343443 |

| Railway Bridge, Childwall Ln, Huyton-with-Roby. | II | 1075531 |

| Railway Bridge, Pilch Ln East, Huyton-with-Roby. | II | 1343466 |

| Railway Bridge, Archway Rd, Huyton-with-Roby. | II | 1075530 |

| Roper's Railway Bridge, Dragon Ln, Whiston. A skew bridge. | II | 1392301 |

| Rainhill Bridge. This skew bridge, on the western side of Rainhill Station, carries Warrington Rd over the railway. | II | 1253244 |

| Rainhill Station, Station Rd. | II | 1391885 |

| Bourne's Tunnel below the railway to the east of Rainhill Station. Built to accommodate a tramway from Sutton Collieries. | II | 1393700 |

| Railway Bridge, Marshall's Cross Rd, St Helens. | II | 1075916 |

| Railway Bridge, Newton St, St Helens. | II | 1075917 |

| St Helens Junction Station, Station Rd. | II | 1437498 |

| Sankey Viaduct. This nine-arched viaduct was built to carry the railway over the Sankey Valley and Canal. | I | 1075927 |

| Building on the south side of Earlstown Station, Railway St. | II | 1343264 |

| Four-arched Newton Viaduct, Mill Ln, Newton-le-Willows. | II | 1283575 |

| Newton-le-Willows Station. | II | 1343248 |

| Memorial to the Rt Hon William Huskisson MP on the south side of the railway near Parkside Rd, Newton-le-Willows. | II | 1075900 |

| Railway Bridge, Worsley Rd, Salford. | II | 1067504 |

| Railway bridge over river Irwell leading to Liverpool Road Station, Manchester. | I | 1270603 |

| Liverpool Road Station and Station Master's House, Manchester. | I | 1291477 |

Further Reading

Carlson, Robert E, 1969. The Liverpool & Manchester Railway Project 1821-1831. Newton Abbot: David & Charles.

Donaghy, Thomas J, 1972. Liverpool & Manchester Railway Operations 1831-1845. Newton Abbot: David & Charles.