Introduction

During the late 17th century Thomas Patten, a Lancashire businessman and merchant, was trading along the river Mersey between Liverpool and Warrington. In order to improve access for his barges to a quay just below

Warrington he cleared some obstructions in the river. In a letter he wrote in Jan 1677, he remarked that it would be an advantage to make the rivers Mersey and Irwell both navigable to Manchester.

At that time there were no proper roads, only muddy and deeply rutted tracks that were frequently impassable in bad weather. These tracks were negotiated by horses hauling waggons and by trains of packhorses.

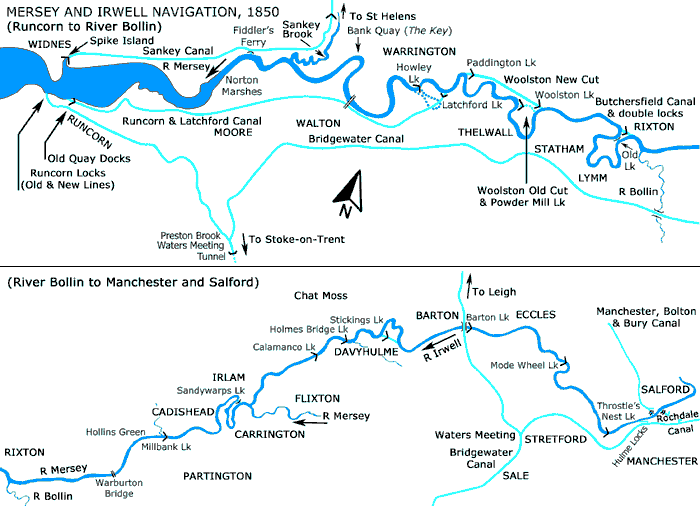

The first known attempt to remedy the situation with the rivers occurred in 1712 when Thomas Steers, a local engineer, surveyed them and published a map showing the location of eight locks and the rise in level at each of them. He also recommended that a cut should be built at Butchersfield to bypass a hairpin bend in the Mersey near Lymm. A number of businessmen in Manchester supported the scheme that Steers was promoting but, owing to a lack of money, events made little progress. He also considered that there could be a possible military use for it.

The conveniences of the Navigation carried thence to Manchester, might one time or another be of the greatest importance in time of War, in Joyning a communication of the East and West Seas of Great Britain with only 28 miles of land carriage.

Eventually, King George I gave the Royal Assent to the Act of Parliament that sanctioned these improvements on the 17 Jun 1721 but it was not until 1724 that work actually started. This Act authorised the promoters to make the rivers navigable between Bank Quay, Warrington, and Hunt's Bank at Manchester and Salford.

Initially 500 shares were issued at £100 each in the Old Quay Company but at one point they reached £1,250, with an annual dividend of £35. Shareholders were afforded the opportunity to take a day trip down to Warrington from Manchester on board a barge with dining facilities.

Construction progress was slow because both the Mersey and Irwell were very winding rivers greatly impeded by shallows and mudbanks. The precise date of the conclusion of this work is unknown. It appears that the rivers were open, after a fashion, in 1734 but the consensus is that it only became fully open sometime in 1736. Some prints, dating from a few years before 1736, show vessels on the rivers but it is likely that these were small craft that had been trading there for some time.

In 1735 Manchester got its first purpose-built quay on the river Irwell. This mooring was 136-yards long and it was built at the end of Quay Street, which was built simultaneously as part of the contract. The contractor was Edward Byrom who was paid £1,200 for the work.

Once open, trade was slow to grow and it is understood that there were only five vessels in use for the first few years. As Thomas Steers had planned in 1712, there were eight locks along the navigation. A short cut was made at Latchford to bypass a hairpin bend in the Mersey, known as the 'Hell Hole', and in association with this Howley Lock, the first one to be built, was positioned in the short cut. Below Howley Lock the river Mersey was tidal. Heading upstream, the eight original locks, built during the 1720s, were:

| Name | Location |

|---|---|

| Howley | Warrington |

| Millbank | Between Partington and Cadishead |

| Calamanco | Flixton |

| Holmes Bridge | Davyhulme |

| Stickings | Davyhulme |

| Barton | Barton-on-Irwell |

| Mode Wheel | Between Eccles and Salford |

| Throstle's Nest | Old Trafford |

Calamanco and Mode Wheel Locks were built at points where weirs already existed, built to supply water to waterwheels at long-established mills. These mills often caused problems for barges by lowering water levels at locks by running too much water into their millraces.

Having got both rivers open for navigation, the next step was to straighten the line of the navigation as much as possible by cutting a number of short canals to bypass the largest of the loops in the rivers. One of these was Woolston Old Cut, which was only half-a-mile long and yet it avoided over two miles of winding river Mersey at Thelwall. A lock, built at its lower end, gave it some protection from floods in the Mersey.

This lock, known as Powder Mill Lock, was built in 1755 and it took its name from the adjoining Thelwall Gunpowder Mills. Similarly, cuts were made at Butchersfield, near Lymm, and at Sandywarps near Irlam. Each cut was provided with a lock, or locks, to overcome differences in river levels. Over the years, many other improvements to the navigation were made and these are summarised below:

Early Years of Operation

When the navigation first opened, merchants were slow in taking up this new means of transportation between Liverpool and Manchester, in spite of the fact that land carriage was

more expensive. Tolls on the navigation had been fixed at 3s 4d per ton for the use of the whole or any part of the navigation, except for marl, dung and manure for use on land within five miles of the rivers.

This charge remained unaltered for about 150 years.

The reason for the slow uptake appears to be the uncertain state of the two rivers and difficulties in navigating them, which led to delays in the delivery of goods. At first, no profits were made and the promoters encouraged trade by investing what money they had into bypassing some of the many bends in the rivers. They were aware that the navigation could only be made prosperous by making it permanently open throughout its length and by keeping it well maintained.

First Competition

Francis Egerton, the Third Duke of Bridgewater, owned vast estates at Worsley, near Manchester, and he wanted to construct a canal to carry coal from his mines at Worsley into

Manchester and Salford. The Mersey and Irwell Company resisted all attempts by the Duke to build his Bridgewater Canal, which included an aqueduct across the river Irwell at Barton. In the event, the Duke's wishes prevailed and

his canal opened on the 17 Jul 1761. Local people flocked to the aqueduct to watch the spectacle of barges on the Bridgewater Canal sailing over the top of barges on the River Irwell. After the Bridgewater Canal was open,

the Duke put plans in place to extend it and the line was driven through Cheshire as far as Runcorn. After overcoming many difficulties this extension opened in early 1776.

Mersey Flats, Trading and Conflicts of Interest

In the 1700s a sailing barge was evolving in the North West that could use the local rivers as well as sail along the Lancashire coast as far as

Lancaster and along the North Wales coast. During the 17th century, Liverpool, which stood on the Mersey Estuary, began to emerge as the premier port in the North West and consequently these distinctive vessels, centred on

Liverpool, became known as 'Mersey Flats'. On the rivers Mersey, Weaver and Douglas, smaller vessels of this type were able to venture as far as the tide allowed them to go but once locks had been built on the

rivers, then they could sail further upstream.

In the early years, these vessels were sailed whenever conditions allowed but when the wind was unfavourable they were hauled by teams of men known as 'bankhauliers'. Later on, after proper towpaths had been built, horses were used instead. Usually, two horses per vessel were used and they were changed at regular intervals. Initially, a Mersey Flat loaded with 30 to 35 tons of cargo drew about three feet of water and this was about the maximum at the time because of the shallows in the rivers. As the condition of the rivers improved, flats could be loaded up to about 80 tons. It is recorded that Mersey Flats had 'brickdust' coloured sails.

The Navigation Company rented accommodation at Liverpool and built warehouses at Warrington and Manchester. Additionally, smaller towns along the two rivers were each provided with a small wharf, as were mills such as at Latchford, Millbank, Calamanco and Mode Wheel.

In spite of competition from the Bridgewater Canal, it was found that there was ample business for both concerns and as the prosperity increased the fleet of Mersey Flats was increased. In 1793, Hugh Henshall, Charles Moniven and Matthew Fletcher, all experienced engineers, examined the locks and other works throughout the navigation and listed all the faults they found and recommended steps that should be taken to put matters right.

Riverside mills were a constant source of conflict, particularly those at Howley, Barton and Mode Wheel whose large waterwheels required large amounts of water. This often resulted in water levels at the weirs being lowered sufficiently for vessels to become grounded. Legal action was sometimes necessary in order to correct this problem. Nevertheless, the main difficulty to navigation remained the tidal section of the river Mersey between Warrington and Runcorn. It had constantly shifting mudbanks and treacherous currents and these factors demanded great skill of the crew in charge of the vessels. The solution to this was the construction of the Runcorn and Latchford Canal, which opened in 1803. This canal was 7¾ miles-long and at Runcorn a river lock was built to allow access. In the 1820s a basin was constructed at Runcorn with a river lock providing access to it and a second lock accessing the canal. Officially, this canal was known as the Runcorn and Latchford Canal but it was also variously known as the Mersey and Irwell Canal, the Old Quay Canal or the Black Bear Canal after a nearby public house.

Over the years trade continued to grow, as did the rivalry with the Bridgewater Canal. Each company would offer reduced freight charges or special rates and concessions to entice traffic away from the other. Probably the most important cargo carried was raw cotton from Liverpool to Manchester but timber, dyewoods, pig iron, lead, copper, nails, tar, sand, grain and flour were all carried. It was a common site to see flats piled 8 or 9 feet high with cotton bales, thus making it difficult for the man at the helm to see where he was going.

Mersey Flats at Liverpool, bound for Runcorn, left Liverpool three or four hours before high water and as many as 50 or 60 would leave with each tide. They sailed upriver and in two or three hours they reached Runcorn. At Runcorn they would divide with some entering the Mersey and Irwell Navigation and others entering the Bridgewater Canal. Some flats used neither and these sailed up the Mersey Estuary itself bound for a variety of destinations such as the river Weaver or the Sankey Canal via the river locks at Widnes (Spike Island) or the river lock at Fiddler's Ferry. Others would proceed to Warrington bound for the wharfs at Bank Quay. Mersey Flats took some 13 to 15 hours for the voyage between Runcorn and Manchester and horses were changed four times along the way. Stables were provided at Runcorn, Latchford Lock, Cadishead and Barton Lock.

It is understood that only two Mersey Flats have survived, Mossdale and Oakdale.

For details of these vessels click here » Mersey Flats

Lock Houses

At first, locks on the two rivers were operated by the flat crews but in Aug 1806 the proprietors decided that lock keepers should be employed to work the locks. This was to enable the Navigation to cope with

increasing usage, which was resulting in damage caused by flats constantly colliding with lock gates and walls or running onto adjacent weirs. This necessitated the construction of lock houses built adjoining the locks.

These were small cottages of simple design having slate roofs and whitewashed walls.

Passenger Services

It was not until 1807 that the company decided to enter the passenger-carrying business in spite of the fact that there had been such a service on the Bridgewater Canal for some years.

Typically, up packets left Runcorn at 10:00am and arrived at New Bayley Street, Manchester, at 6:00pm. Similarly, down packets left New Bayley Street, Manchester, at 8:00am and arrived at Runcorn at 4:00pm.

In 1816, the first packet steamers arrived, one of these being the Prince Regent.

On the 15 Sep 1830 the Liverpool and Manchester Railway opened and thereafter packet-boat services went into decline and they ceased operating in the 1860s.

Floods

Most times, the rivers Mersey and Irwell flowed peacefully along their meandering courses but this was not always the case. Whenever there was very heavy rainfall in the Pennine hills this quickly swelled the

many streams that fed these rivers with vast amounts of water. The situation was especially serious in Manchester and Salford where the river Irwell narrows and its banks were crowded with mills, factories and wharfs.

These natural and man-made constrictions caused the water level in the river to rise rapidly, creating flooding, havoc and panic. Records as far back as 1616 show that this happened annually. In 1825 six towhorses were

drowned but the worst flood recorded occurred on the 13 Nov 1866. This caused the Irwell to rise by 14 feet. Boats rescued 700 people, 3,500 houses and 40 mills and factories were flooded as well as 2,000 acres of

surrounding land. One of the last serious floods to occur happened in 1946.

Decline and Fall

In 1845, Lord Ellesmere bought out the Navigation for £550,800 and the purchase was then transferred to the Bridgewater (Canal) Trustees. In 1872, both the Mersey and Irwell Navigation and the Bridgewater Canal were

bought out by a railway syndicate for £1,120,000. In 1882, a Committee, led by Daniel Adamson, formed the Ship Canal Company.

Daniel Adamson was the first chairman of the Manchester Ship Canal Company. In 1883, their application for the construction of a Ship Canal failed and it was recorded that the

Navigation was virtually unused and semi-derelict. In 1884, an application for a second Act for a Ship Canal was made and this too failed. A third application was made in 1885 and this passed.

(5 Aug 1885, The Manchester Ship Canal Act, 48 & 49 Vict.) and work commenced in 1887.

Both the Mersey and Irwell Navigation and the Bridgewater Canal were taken over by the Ship Canal Company for £1,710,000 and the first sod of the Ship Canal was cut at Eastham on the Mersey Estuary.

Between 1887 and 1893, the course of the Mersey and Irwell Navigation was largely absorbed by excavations for the Ship Canal. On the 1 Jan 1894, Queen Victoria formally opened Manchester Ship Canal.

The lower reach of the Navigation, between Runcorn and the river Bollin, more or less survived construction of the Ship Canal and it was still used. Indeed, the last vessel to navigate Woolston New Cut did so in the early 1950s. Between the river Bollin and Manchester and Salford the scene was very different. The Ship Canal followed the line of the Navigation in a smooth arc, leaving only short sections of isolated river bed at Warburton, Partington, Irlam and Stickings.

Officially, there were four sections of the Mersey and Irwell Navigation after the Ship Canal opened, one being new, all under the jurisdiction of the Manchester Ship Canal Company. These were:

Alternative names of the Mersey and Irwell Navigation

The Navigation was referred to by a variety of alternative names and the following is a list of those that have been identified:

The 'New Quay Company' should not be confused with the 'Old Quay Company'. The former was a company based in Manchester that was founded in 1823. It was an independent canal carrier on the Mersey and Irwell Navigation, mainly specialising in carrying shop goods.

| Name | Original Locks (1720s) | Later Locks (Post 1720s) | Rise | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Old Quay Sea | 1804 | Variable | One lock accessing the Runcorn & Latchford Canal. | |

| Old Quay Sea | 1820s | Variable | Two locks accessing the Runcorn & Latchford Canal. The lock of 1804 was retained. | |

| Latchford | 1804 | 4ft 8in (fall) | ||

| Howley Tidal | 1 | Variable | ||

| Woolston Old | 1755 | 5ft 0in | ||

| Paddington | 1821 | 3ft 8in | Lower end of Woolston New Cut | |

| Woolston New | 1821 | 3ft 8in | Upper end of Woolston New Cut | |

| Butchersfield | c.1760 | 2ft 5in | ||

| Butchersfield Double | 1829 | 2ft 5in | Locks side-by-side on the Butchersfield Canal. These replaced the single lock of c.1760 | |

| Millbank | 2 | 6ft 6in | ||

| Sandywarps | c.1760 | 6in (about) | ||

| Calamanco | 3 | 3ft 3in | Rebuilt in 1820 | |

| Holmes Bridge | 4 | 5ft 2in | ||

| Stickings | 5 | 4ft 4in | ||

| Stickings | 1832 | 4ft 4in | On a new cut | |

| Barton | 6 | 5ft 9in | ||

| Mode Wheel | 7 | 5ft 10in | ||

| Throstle's Nest | 8 | 7ft 6in |

Dimensions of Locks

Locks on the Mersey and Irwell Navigation were all built to accommodate Mersey Flats and it is understood that the eight original locks were each 68 feet long by 16 feet 4 inches wide.

These were later extended to 72 feet 8 inches long and the later locks were also built with this length. Earlier flats seemed to be 66 feet long by 15 feet 6 inches beam but later they were up to

about 70 feet long by 14 feet 3 inches to 15 feet 9 inches beam.

| Name | Miles | Furlongs |

|---|---|---|

| Bank Quay (Entrance Basin, Locks & Warehouse) to: | — | — |

| Arpley Railway Viaduct | 2 | 1 |

| Warrington Bridge | 2 | 4 |

| Howley Lock and Weir | 2 | 6 |

| Howley Quay | 3 | 1 |

| Latchford Lock (Runcorn & Latchford Canal) | 3 | 3 |

| Paddington Lock (Woolston New Cut) | 4 | 1 |

| Woolston Lock (Woolston New Cut) | 5 | 5 |

| Statham Lane | 6 | 1 |

| Butchersfield Double Locks | 6 | 7½ |

| Butchersfield Canal (Top entrance) | 7 | 1 |

| Warburton Bridge | 8 | 7 |

| Hollins Ferry | 9 | 5 |

| Millbank Ferry & Paper Mill | 9 | 7 |

| Sandywarps Lock | 11 | 7 |

| Junction of Rivers Mersey and Irwell | 12 | 0 |

| Irlam Ferry | 13 | 0 |

| Name | Miles | Furlongs |

|---|---|---|

| Calamanco Lock & Mill | 13 | 5 |

| Holmes Bridge Lock | 14 | 1 |

| Stickings Lock & Cut | 15 | 1 |

| Barton Lock & Aqueduct (Bridgewater Canal over River Irwell) | 16 | 5 |

| Trafford Hall | 16 | 7 |

| Mode Wheel Lock | 18 | 5 |

| Throstle's Nest Lock | 20 | 0 |

| Pomona Gardens | 20 | 4 |

| Woden Street Footbridge | 20 | 7 |

| Hulme Locks Branch Canal (connection with Bridgewater Canal) | 21 | 0 |

| Regent Bridge | 21 | 1 |

| Princess Bridge and connection with Manchester, Bolton & Bury Canal | 21 | 2 |

| Old Quay Yards & Irwell Street Bridge | 21 | 3 |

| Albert Bridge | 21 | 5 |

| Blackfriars Bridge | 21 | 7 |

| Victoria Bridge | 22 | 0 |

| Hunts Bank | 22 | 1 |

Click thumbnails for full pictures, then click browser back button/arrow to return here