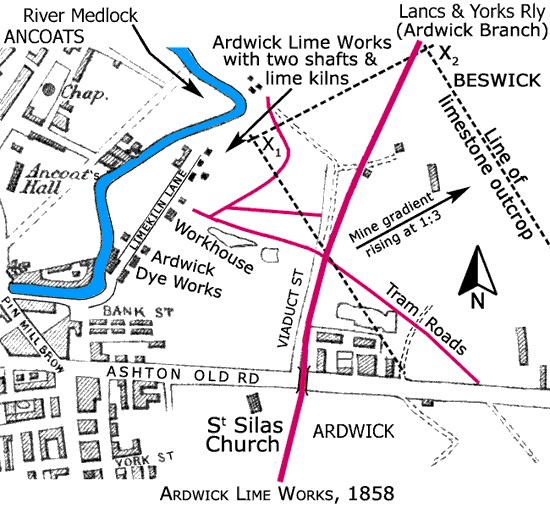

Ardwick Lime Works was sited over an outcrop of limestone lying to the east of the river Medlock and north of Ashton Old Road. Access to the works was along Limekiln Lane from Pin Mill Brow. A map of East Manchester for 1848 shows that the lime works was established by this time but there are indications that limestone was being extracted here much earlier than this.

There is evidence that the Romans extracted limestone in Ardwick for the manufacture of mortar. Analysis of half-burnt limestone from the Roman period in Manchester showed the presence of spirobis (very small worms with white coiled shells), which is characteristic of Ardwick limestone. Additionally, Mr Mellor, a former manager at Ardwick Lime Works, stated in a paper read to the Manchester Geological Society, that in one of the older workings old Roman mining tools were found. In 1322 mention was made of the ‘kiln at the Ancoates’ and of a ‘stany gate’ (‘stoneygate’ or ‘stone road’) leading to it (NoteRoeder, C, 1900. Transactions of the Lancashire and Cheshire Antiquarian Society, Recent Discoveries in Deansgate and on Hunt’s Bank and Roman Manchester (1897-1900), pp. 87-212, Vol. XVII. Manchester: Richard Gill.).

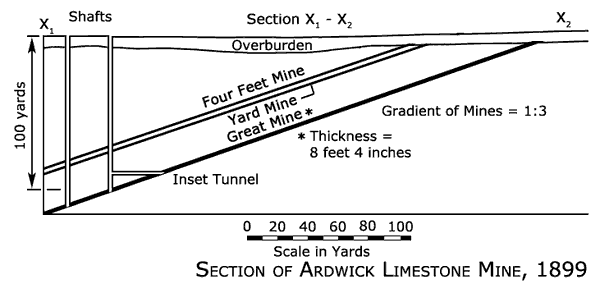

The two main shafts were sunk through three seams of limestone in the outcrop. In order of depth these were the Four Feet Mine, Yard Mine and Great Mine. The latter was the thickest seam at 8 feet 4 inches and consequently it was the most important. This was reached at a depth of about 100 yards. From the shafts the seams rose at a gradient of 1:3 in an easterly direction.

Ardwick Lime Works was last operated by Messrs William Brocklehurst & Co and a mine plan (NoteOates?, J A, Sep 1899. Plan of the Great Mine Workings. Radcliffe: Messrs J Grundy & Sons, Mining Engineers.) recorded that on the 22 November 1888 limestone extraction in the Great Mine ceased. Following this the works went into decline and in 1896 the Mine Inspector for the Manchester District, John Gerrard, recorded that the company had just one employee working underground. This implies that the works was probably closed by this time.

The limestone outcrop at Ardwick is embedded in the Upper Coal Measure and an analysis of c.1839 found that it consisted of Calcium carbonate (84%), Magnesium carbonate (2%), Aluminium oxide (4%), Ferrous oxide (5%) and residue (5%). The residue would have contained silica (Silicon dioxide) and other trace elements. This type of limestone, when burnt in a kiln, produces a natural hydraulic lime after slaking with water. It is the presence of silica and other trace elements that causes the hydraulic set of mortar made with it.

Map of 1858 with the limestone outcrop overlaid on it showing its extent and rise to the east at a gradient of 1:3. See Section X1 - X2 on the diagram below.

The lime works had a system of tram roads that connected various features of the complex together. These features are not shown on this map but it is known that they consisted of:

Section of the limestone mine dated 1899, probably after its closure, showing that the easternmost shaft had a horizontal inset tunnel to the Great Mine. The purpose of this was to increase the number of limestone faces that could be worked simultaneously.