Arden Mill is situated on Arden Rd, Bredbury, by the river Tame. Arden Rd leaves Ashton Rd by the Arden Arms public house, the road being paved with gritstone setts.

In 1812 a gang of men attacked Arden Corn Mill. Apparently, they were Luddites and it seems as though their plan was to acquire flour made there using machinery. The miller at the time was Joseph Clay and, after threatening him, they removed the flour and sold it cheaply to people living close by. The militia, in the form of the Scots Greys, was summoned and they arrested four men, Thomas Burgess (35), a collier from Bredbury, Thomas Etchells (34), Samuel Lees (32), and James Ratcliffe (22), all hatters from Denton. In spite of being shot at, a fifth man, Nathan Howard, managed to escape by jumping over the mill weir. He later emigrated to evade capture and punishment.

The four men appeared before magistrates at Stockport where they were committed for trial at Chester, along with another 18 men who had been captured at Bolton, Congleton, Hyde and Wilmslow. All but two were convicted and the four men who attacked Arden Corn Mill were each fined one shilling and sentenced to seven years transportation to a penal colony. The prisoners were taken from Chester to Woolwich where they were handed over to the master of the Retribution Hulk and at this point they disappeared from history.

Another early reference to Arden Mill appeared in the Manchester Times and Gazette on the 29 Sep 1832. It was reported that Joseph Clay of Arden Mill was awarded a Silver Medal by the Manchester Agricultural Society for improving seven acres of land by floating (?). Another reference in 1840 concerns the will of John Higginson, a Miller of Arden Mills, Bredbury.Once Arden Mill had ceased being used for corn milling it was converted into a paper mill. By 1885 the mill was occupied by John Lomax, a paper maker. By 1902 the mill was occupied by the firm of Lancaster, Ferguson & Co, trading as paper makers and merchants, and the proprietors were William Lancaster and Archibald Ferguson. On the 31 Dec 1902 this partnership was dissolved but the firm continued trading under the style of William Lancaster & Co with William Lancaster as the sole proprietor. After the outbreak of the Great War in 1914 its use was to change again in aid of the war effort.

Arden Mill

Bredbury, Cheshire

Grid Ref: SJ 926 934

Tithe Map: 1841, Ref: EDT 63/2

Courtesy: Cheshire Archives & Local Studies

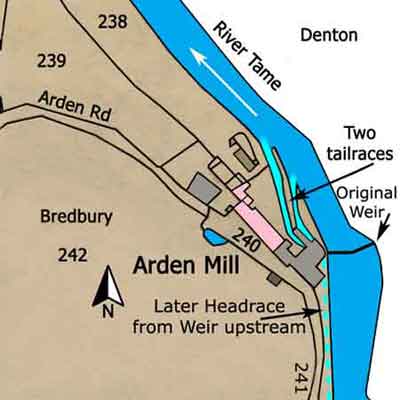

The tithe map shows the mill in 1841 and it will be seen that two tailraces returned spent water back to the river but the headrace is not shown. The mill was fitted with three waterwheels and some technical details of these are shown in the two newspaper cuttings below, dated the 25 Apr 1846 and 24 Jul 1852 respectively. It is possible that the line drawn across the river adjacent to the mill may be the original weir that was removed when the weir further upstream was built. A map of 1848 confirms there was a weir across the river at this point and the 1841 tithe map does not show a weir further upstream at the site of the present weir.

The Apportionments accompanying the tithe map shows that the Trustees of Ellis Fletcher (James Moore, Thomas Mulliner and Jacob Fletcher Ramsden) owned the land hereabouts and the occupier was Joseph Clay. There was a house close to Arden Mill that was occupied for a while by Peter Rothwell who was the Agent of the Proprietor of Ellis Pit (Denton Colliery) and it was also used by coal miners who had arrived from the Clifton and Worsley area of Lancashire to work in local pits owned by the Trustees. Mill Field was a large field adjoining Arden Mill in Bredbury and it is likely that Mill Field House (or Mill Fold), where Peter Rothwell and the miners lived, was the farm (or near the farm) now known as Mill Hill Farm.

The plot details are as follows:

| Plot No. | Plot Name |

|---|---|

| 238 | Garden |

| 239 | Little Meadow |

| 240 | Arden Mill |

| 241 | Waste |

| 242 | Mill Field |

Joseph Clay (1774-1859), the Miller at Arden Mill, was born in Chapeltown, Sheffield, Yorkshire, and the 1851 census shows that he was then living at Woodley Cottage,Stockport Rd. He gave his occupation as a Master Miller employing six men.

Some water-powered mills were not located directly on river banks in order to build them on more convenient sites and in the case of Arden Mill it was built on Arden Rd, where it could be served by a millrace supplied with water from a weir built across the river. In order to increase the head of water, the present weir (Arden Mill Weir) was built across the river approximately 550 yards upstream of the mill site. It is understood that the millrace was 10 feet wide by 3 feet deep. The date when this was constructed is unknown but it was certainly there by c.1875.

The headrace from this weir to the mill was cut along the left bank of the river and parallel to it. The tailrace, used to return spent water back into the river, was relatively short when compared with the length of the headrace. An input sluice was provided by Arden Mill Weir, which was used to control the amount of water flowing into the headrace. A short distance below this an overflow sluice was provided for use in the event of flooding, so that surplus water could be discharged back into the river.

Arden Mill Weir, Jan 1950.

Arden Mill Weir, Jan 1950. Arden Mill and Weir, 1897.

Arden Mill and Weir, 1897.The type of waterwheels initially used to power the mill is unknown but from the lie of the land at the mill site it is likely that they were breastshot from which line shafts and mitre gears would transmit power into the mill. Typically, a breastshot waterwheel is powered by a head of water entering the wheel at a position between one third and two thirds of the wheel diameter measured from the lowest point of the wheel. This causes the wheel to rotate in a direction opposite to that of the flow of water in the mill race or leat.

Breastshot Waterwheel.

During the 19th century, corn grinding went into decline in the area and sometime after 1852, when it ceased to be a corn mill, it was converted into a paper mill. Freeman's Journal and Daily Commercial Advertiser for the 22 Feb 1865 confirms that by then it was operating as a paper mill. At this time the proprietors were Heywood, Higginbottom, Smith and Co Ltd of 15 Parliament St, Dublin.

An interesting development at the mill was the introduction of two water turbines to supply power. It is not known when this happened but it is likely that it occurred prior to the outbreak of the Great War in 1914 or early in the war. This new source of power may have been introduced in association with the third change in use of the mill. From the external appearance of these turbines, it is likely that they were of the mixed flow reaction type in that they combined radial and axial flow. This meant that water entered the runner (rotating part like a propeller) radially and left it axially. Water turbines of this type can be over 90% efficient and they usually operate at heads of water of between 6 feet and 660 feet. The first modern water turbine was invented by Fourneyron in 1830 but since then other engineers have introduced variations to the original concept. The most important of these was the Francis turbine, invented by the American engineer, James Bichiro Francis, in 1840. However, the turbines at Arden Mill lack the typical spiral outer case of the Francis turbine, so they must have been one of the other types. In use, an electrical generator was attached to the runner shaft to form a single unit. It is understood that these turbines generated up to 300 hp (224kW) and they powered the mill as well and an adjoining row of cottages.

|

|

The two water turbines, 1971. Water from the headrace entered the turbines, radially, through the two pipes in the background. This was then discharged, axially, to pass into the tailrace through the two pipes in the foreground. |

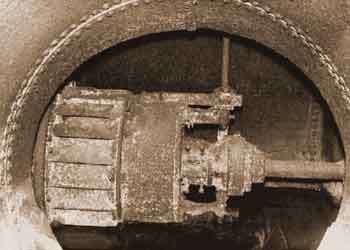

Detail of the water turbines, 1971. This view is possibly from the headrace side looking inside the turbine on the right in the first view. It may show one of the generators, which would have been submerged in use. |

|

|

Detail of the water turbines, 1971. Possibly, these are the penstocks (sluice mechanisms) used to control the flow of water to the turbines. |

The tailrace from the water turbines is in the background on the right, behind the stone wall, 1950s. The large boulder in the river Tame is known as the Robin Hood Stone. |

|

Arden Mill viewed from the river Tame looking downstream, early 20th century. |

Contemporary local sources all agreed that the last change of use at Arden Mill involved the manufacture of guncotton. However, it is more likely that it was proposed to manufacture a similar but more modern material known as cordite. The chemist, Sir Frederick Augustus Abel (1827-1902), improved the manufacture of guncotton by the careful preparation of nitrated cotton to produce a fine pulp and this was complemented by the introduction of much longer washing and drying times. Then, in association with the chemist and physicist, Sir James Dewar (1842-1923), he developed cordite, which was the type adopted by the British Government in 1891.

It is now known that in Aug 1917 Arden Mill was requisitioned by the Government as 'His Majesty's Cotton Waste Mill'. It was No. 153 of 218 National Factories established as a result of the Munitions of War Act, 1915 (5 & 6 George V cap 54). It was controlled by the Ministry of Munitions, which operated between Jun 1915 and Nov 1918, through the British and Foreign Supply Association. It was known as, No. 153, Woodley, Arden Mill DRB - Cotton Waste. Although it was requisitioned in Aug 1917 there is no record of the date of its first output. This implies that the large explosion that destroyed it occurred while the mill was still undergoing conversion to its new use, following which it was abandoned.

Subsequently, the millrace became blocked and overgrown and the sluices rotted away. In the 1950s it was still possible to see alongside Arden Mill weir a gear wheel and shaft once used to operate the inlet sluice, as well as traces of the overflow sluice.

Surprisingly, the water turbines remained in situ until the early 1970s. They were best seen from the footpath on the opposite side of the river Tame where, with care, their distinctive shape could be discerned through the foliage. Their fate is unknown.